Summary

Following the Second World War, the Allied Powers attempted the largest-scale technology transfer effort in history, aiming to take “intellectual reparations” from occupied Germany. This book is a history of America, British, French, and Soviet cooperation and competition in controlling and exploiting German science and technology. Through this, it is a history of science, diplomacy, espionage, and changing attitudes towards technology in society.

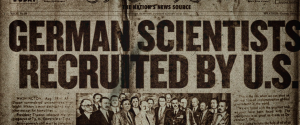

One dimension of this story is fairly well-known: Project Paperclip, which brought over the Nazi rocket scientists who helped NASA with the moon landings, led by Wernher von Braun. The Nazi scientist working for the West became a cultural archetype in fiction from Dr. Strangelove to Captain America. Paperclip is only one relatively small episode in the American case, however. This book reveals the inner workings of an international set of programs with much broader ambitions than rocket science. In nearly every field of industrial science and technological research, the Western allies gathered teams of experts to scour defeated Germany, seeking industrial secrets and the technical personnel who could explain them.

This book addresses two major gaps in the sparse academic literature on these efforts. First, almost all of the current literature on this topic looks solely at the American case, limiting our knowledge to the perspective of the country with the least to gain from German technology. The United States emerged from the war with excess industrial capacity and a mobilized, world-class scientific community, unlike indebted Britain, recently-occupied France, or the shattered Soviet Union. Second, this literature tends to accept claims of technology being “taken” at face value, skipping over the enormous challenges of effectively communicating and implementing technology across national and cultural borders. The greatest espionage coup in the world is useless if no one uses the information it provides.

By taking a transnational perspective, this book emphasizes how these ambitions filtered through the different diplomatic, political, and economic circumstances of the three main Western Allies. It takes a careful approach to the question of technology transfer. What exactly did planners in each country expect to acquire from studying Germany, and why did they expect that? How did they intend to take science and technology? Were they successful, as judged by the businessmen and trade associations involved? These issues played out very differently in each nation, with early Cold War diplomatic tension driving and being driven by different approaches to learning from German science. The legacies of the efforts to take German technology lay not just in economic gains, but in the international politics and business culture of the early Cold War.

The overarching argument of the book is that the late 1940s and early 1950s witnessed a dramatic change in international understanding of what it means to transfer technology. While America and Britain initially planned on sharing German technology with their industries via written reports, they increasingly found themselves in agreement with a stance already held by many in France and the Soviet Union: technology cannot be separated from the technical ‘know-how,’ the hands-on skill and experience of technicians and engineers, that cannot be captured in writing. This meant rapid and fundamental changes in the exploitation programs, with significant diplomatic costs. It also left a lasting impression on the businessmen across the Western world, who had been brought in to staff these programs and select targets of economic value. Moving technology across national and cultural borders meant moving people – a lesson with long-lasting implications for business, law, and intelligence agencies in an increasingly global postwar economy.

Praise for Taking Nazi Technology

"[U]tterly rooted in scholarly rigor ... [F]ascinating. ... [R]eaders with very little prior knowledge [can] engage with the narrative. ... [A] story that has not been widely told before"

-Science magazine

"An important book. Taking Nazi Technology will appeal to general readers, as well as historians of science and technology, the Cold War, economic history, and information science."

(Brian E. Crim, University of Lynchburg, author of Our Germans: Project Paperclip and the National Security State)

"A fascinating study of the different strategies adopted by the occupying powers in postwar Germany to appropriate science and technology, read through the lens of technology transfer and the acquisition of knowhow."

(John Krige, Georgia Institute of Technology, author of Sharing Knowledge, Shaping Europe: US Technological Collaboration and Nonproliferation)

"This is an ambitious book that challenges conventional thinking about scientific practice, technology transfer, and the elusive question of 'know-how.' Efforts by Allied nations after World War II to capitalize on German expertise triggered enormous changes in everything from science policy to how we store and sift information. A wide-ranging and engrossing study."

(David Kaiser, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, author of How the Hippies Saved Physics: Science, Counterculture, and the Quantum Revival)

"Taking Nazi Technology, a new book from Douglas O'Reagan, details what the Americans found when they began looting Nazi Germany... At a time when the United States has become deeply insecure about its technological leadership, the story has important lessons for policymakers."

(Robert Farley, National Interest)

Reader reviews on Amazon.com and Goodreads:

"The book a fascinating and well researched account of a little known but important aspect of post WWII history. I typically do not gravitate towards history books, but I found the book and topic deeply engaging. I would especially recommend it to those with interests in history, history of science, and intellectual property. So glad I happened upon Mr. O'Regan's presentation because this has been one of my favorite reads of the year so far. I plan to give a copy to a few colleagues as well."

"I am not the most well versed person in the history field, particularly military history, but this book was fascinating and did not require any background knowledge on the topic. The details and context are very clearly setup throughout the book. This is also an area I do not think most people heavily consider (transfer of technology that occurs during war), so I think many people will find this book rather eyeopening (as I did). The author's storytelling ability with a very technical subject is impressive, making this a very easy yet still rich and dense read. I could not put it down!!"

"I'm a fan of history but don't often read history books as I find them too academic - I got this as a gift and highly enjoyed it. This was a fast paced and readable book and the topic is absolutely fascinating. A great history through an interesting and little thought of field."

"Fascinating accounting of technologies developed and utilized from the Nazi's in World War II. Well researched and written, the book is interesting and educational. Thought provoking too."

This book is based on my PhD dissertation, “Science, Technology, and Know-How: Exploitation of German Science and the Challenges of Technology Transfer in the Postwar World” (available in full at this link).

Part of one chapter, exploring the French exploitation of German science, became an article published in the International History Review: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07075332.2013.879917

Part of another chapter, looking at the broader history of business interest in “know-how,” became an article in Technology and Culture: https://muse.jhu.edu/article/648252/